Past Projects

Indicators of Sex Trafficking in Online Escort Ads

Background

Law enforcement and prosecutors have long used online escort advertisements to identify sex trafficking victims and investigate cases. Several ad characteristics are used and shared among investigators as signs of trafficking, but they have not yet been empirically tested for predictive power to support investigative decisions or the use of ads as evidence in court.

Study Objectives

To improve victim identification and investigations, this National Institute of Justice-funded study had two objectives:

1. Investigate whether there were indicators that could be used to differentiate online escort ads related to sex trafficking from ads associated with consensual sex work.

2. Determine which indicators were most likely to predict whether the ad represented a trafficking case.

Indicators of Sex Trafficking in Online Escort Ads Research Brief

Study Goal

The goal was to create guidance that investigators can use to help focus limited investigational resources on ads more likely to represent a trafficking victim.

Law Enforcement Guide on Indicators of Sex Trafficking in Online Escort Ads

Law Enforcement Pocket Guide on Indicators of Sex Trafficking in Online Escort Ads

This card is a printable, pocket-sized guide for law enforcement officers intended to improve their identification of trafficking victims. The card is 3″ x 4″ in size to accommodate easy pocket carry. (Instructions: Print the card out double-sided, flip on the long edge, cut out, and fold in half.)

This project had three parts:

1. Analyze ads from closed cases from a variety of U.S. jurisdictions, supplemented by ads from three web scraper archives;

2. interview investigators to learn how they use ads in investigations; and

3. conduct focus groups with three stakeholder groups at the beginning and end of the project:

-

-

-

-

-

- sex trafficking survivors,

- consensual (non-trafficked) sex workers, and

- criminal justice/victim advocate professionals.

-

-

-

-

Fieldwork sites included

- San Diego District Attorney’s Office (SDDA)

- San Francisco District Attorney’s Office (SFDA)

- Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI)

- Texas Department of Public Safety (TXDPS)

- Nebraska State Patrol and Nebraska Attorney General, with help from HTI Labs at Creighton University

- Additional ads from three more states (OR, NM, and NY), mostly for massage cases, were provided from a”ground truth” set held at Claremont Graduate School

Indicators that Predicted Sex Trafficking

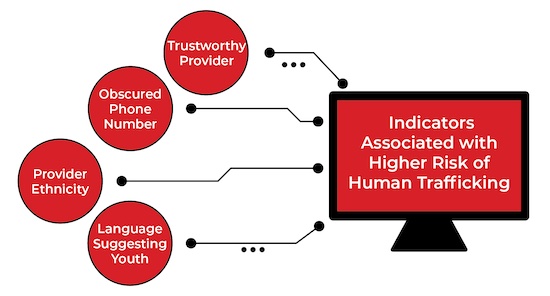

We tested 27 potential indicators derived from the literature, focus groups, interviews, and fieldwork. Four indicators emerged as strongly predictive of sex trafficking when compared to ads for consensual sex work, controlling for the effects of other indicators that might be in the ad:

1. Obscured phone number. Using obfuscation techniques to evade law enforcement or web scrapers, such as emojis between numerals or spelling out numbers, increased the likelihood of trafficking by almost 12 times. But, this was not significant in massage ads.

2. Provider ethnicity listed in ad was over 5 times as likely to represent a trafficking case. However, this was not a significant correlate in massage ads.

3. Trustworthy Provider language (i.e., professional, photos 100% me, discreet) was over 4 times more likely to signify trafficking in fieldwork ads and 20% more likely in massage ads

4. Language suggesting youth (use with caution) increased the likelihood that a case was a trafficking case by over four times. However, the significance of this indicator may also be an effect of collecting data on cases from law enforcement, who already use this language to decide which cases to investigate—thus raising the possibility that its effect is exaggerated in our sample. We recommend use of this indicator with caution, as non-trafficked sex workers also use this language for marketing purposes.

“Looking young.” One photo indicator was statistically significant – the subject looking young – but not as expected. This indicator occurred in three to four times as many non-trafficking or outcome unknown ads as trafficking ads, the opposite pattern expected by investigators. Minors are often made to look over 18 using cosmetics and older individuals may use filters to look younger. Furthermore, photos do not always match the person advertised. Given that one of the top indicators cited by investigators when deciding which ads to pursue is whether the subject in the photo “looks young,” this should prompt a re-thinking of using “youthful appearance” as a decision criterion.

When controlling for other indicators and tested against ads known not to be part of a trafficking case, several commonly-used indicators were not statistically significant predictors of trafficking. Some of these included a stated age under 23, controlled movement language, and movement language. In most instances, these results bore out our consensual sex worker group input that these indicators can serve unrelated marketing purposes or might indicate a consensual provider asserting control over terms of engagement. For more information, download this Research brief.

Recommendations for Use with Other Evidence

Few indicator combinations (interactions) yielded results that would support their inclusion in statistical models using our data. However, there are indicator combinations – especially cross-ad dynamics combined with external, non-ad evidence – that may be more suggestive of trafficking than any single indicator. For example:

1. Three or more providers traveling in a large group who do not appear to know the established circuit, move every 3-4 days, and/or who do not have means for transporting themselves. Investigating these cases takes detailed knowledge of local and regional markets, and the ability to connect individuals across ads.

2. Advertising prices lower than average for the market. This may be more difficult to spot given the frequency with which providers copy each other’s ads—especially if they are inexperienced. Must be combined with other evidence.

This information is intended as a tool that investigators can use to narrow their focus when seeking to identify potential trafficking victims in escort ads. While we hope our results provide useful information for initial victim identification by both investigators and by web scraper administrators and algorithm developers that support them, this information is best used in conjunction with other evidence to more accurately determine whether a case involves human trafficking.

Investigators should also look at other online venues that have increased in popularity with the shutdown of Backpage in 2018 and in response to COVID-19 impacts on the nature of commercial sex activity. These include the movement of some activity further online into video sites or more open solicitation on social media that may begin with public posts and move to encrypted private chatrooms and messaging.

Future research should extend this work to test its applicability to content on these platforms and in studies with larger data sets of ads associated with confirmed cases.

Interested in joining the conversation? Come join us on our discussion boards, where you can talk to colleagues and the researchers about this important topic.

For more information, contact Roger K. Przybylski at rprzybylski@jirn.org.